Department of 1Laboratory Medicine, Division of Pathology, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, Departments of 2Pathology and 5Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA, 3Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Pablo Tobon Uribe and Clinica Medellin, 4Clinical Epidemiology, Hospital Pablo Tobon Uribe and Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, Medellin, Colombia.

OBJECTIVE: In pregnant women, the pituitary is enlarged and the prolactin (PRL) secreting cells increase in size and number. This PRL cell hyperplasia is associated with hyperprolactinemia. The aim of the present work was to investigate adenohypophysial vascularization and immunoexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in pituitaries of pregnant and post-partum women and compare the results with age-matched adenohypophyses of non-pregnant women who had no endocrine diseases. DESIGN: Pituitaries (n=18) obtained by autopsy from female patients of reproductive age who had died during pregnancy, after abortion or during post-partum were immunostained for CD-34 and VEGF using the streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method. RESULTS: The results showed that microvessel densities and VEGF immunoexpression in the adenohypophyses of pregnant and post-partum women were similar to those found in the control pituitaries. CONCLUSION: It can be concluded that pituitary enlargement and PRL cell hyperplasia in pregnant women may occur without neovascularization and increased VEGF immunoexpression.

Angiogenesis, Immunohistochemistry, Pituitary, Pregnancy, Vascular endothelial growth factor

INTRODUCTION

Several well defined morphologic alterations occur in the human adenohypophysis during pregnancy. It was conclusively documented that the pituitaries of pregnant women are increased in size and weight.1,2 Histologic, immunohistochemical, electron microscopic and in-situ hybridization studies provided evidence that there is a significant increase in size and number of prolactin (PRL) producing cells.1,3,4 Now, it is well known that these cells, previously called “Schwangerschaft-Zellen” or “pregnancy cells”,3,5 are PRL producing lactotrophs and the PRL cell hyperplasia is accompanied by increased blood PRL levels.6,7 It was also demonstrated that, besides the increase in the number of PRL producing cells, the numbers of growth hormone (GH) and follicle stimulating hormone/luteinizing hormone (FSH/LH) producing cells are reduced.8,9 The PRL cell hyperplasia is due to multiplication of PRL cells but also to transformation of GH cells to PRL cells.3,9,10 Since blood supply can modify cellular activity, in the present work we investigated microvessel densities (MVD) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) immunoexpression in autopsy obtained adenohypophyses of pregnant or post-partum women and compared the findings with those of non-pregnant age-matched controls.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Eighteen cases of female patients of reproductive age who had died during pregnancy, after abortion or during post-partum, were selected from the Mayo Clinic tissue registry. The age ranged between 16-42 years (Table 1). The pituitaries were collected during autopsy, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, routinely processed, embedded in paraffin and cut at 5 µm. In addition, 15 sex and age-matched non-tumorous autopsy obtained pituitaries of non-pregnant women with no endocrine diseases were also collected and used as controls.

Stains included hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and the periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) method. All cases were immunostained for the full spectrum of adenohypophysial hormones including GH, PRL, adrenocorticotrophin (ACTH), thyrotrophin (TSH), LH and FSH and the alpha subunit of the glycoprotein hormones. Antibody sources and specifications have been previously reported.11

Vascularization of the pituitaries was determined immunohistochemically. Staining directed against CD-34 (Dakocytomation, Glostrup, Denmark; monoclonal antibody; dilution: 1:100) and VEGF (Oncogene Research Products, Cambridge, MA, USA; dilution: 1:100). After routine deparaffinization, rehydration and blocking of endogenous peroxidase activity, sections were pretreated for the purpose of antigen retrieval by means of microwaving in 0.1mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Subsequently, treated slides were incubated with antisera and then exposed to the streptavidin-biotin peroxidase complex. Diaminobenzidine served as chromogen. The CD-34 immunostained sections were analyzed using a computer image analysis system (KS400). For CD-34, microvessel density or percentage of pituitary tissue occupied by vessels, excluding posterior lobe, was determined by measuring their cumulative area in each field. These counts were performed using an Axioplan 2 microscope attached through a 0.63 c-mount to an AxioCam color digital camera. Images were taken using a 10x objective and were captured digitally at a resolution of 1300x1030 pixels. Non-overlapping fields were captured over the tissue section for each pituitary case.12

VEGF expression was assessed semiquantitatively by counting the total number of cells of the pregnancy pituitaries and non-pregnant pituitaries and calculating the percentage of cells with cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for VEGF, regardless of intensity of staining. All parameters were determined independently by three authors (FR, AR and KK).13

Data were tested for statistical significance using the SPSS version 18 statistical computer program (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Ill). All categorical variables were presented as relative and absolute frequencies; quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range according to whether they were normally distributed or not. Comparisons of medians between two independent groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.11-13

RESULTS

By light microscopy, on the H&E, PAS-stained and immunostained sections, no abnormalities, except the increased number or of large lactotrophs with vacuolated cytoplasm, were apparent in the adenohypophyses of pregnant or post-partum women. Immunostaining for adenohypophysial hormones revealed an increase in the size and numbers of PRL- immunopositive cells as compared to those of the age-matched (except for 3 cases) non-pregnant controls. The number of GH- immunoreactive cells decreased, while no change in cell size and staining characteristics was apparent. Immunostaining for LH demonstrated a decrease in the number of gonadotrophs, while the size of the LH- immunopositive cells appeared unchanged. No specific alterations were noted in cell size and number of corticotrophs and thyrotrophs. These results were reported in a previous publication.1

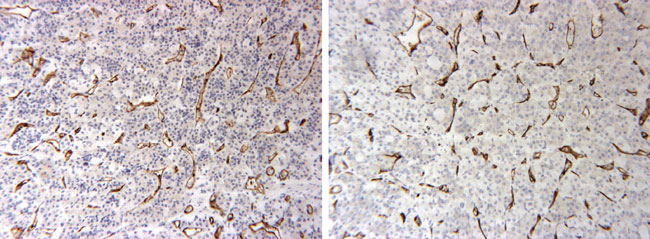

CD-34 immunostaining demonstrated immunopositivity confined to endothelial cells. Immunopositivity was well defined and easy to quantify. In comparison to those cases that had age-matched (range: 16-42 years) pituitaries of non-pregnant women, no significant differences were noted in microvessel density (p=0.42). It was also noted that statistically significant results were obtained when comparing the two groups for stain area/sq μm (p=0.034) and tissue area/sq μm (p=0.043) (Table 2).

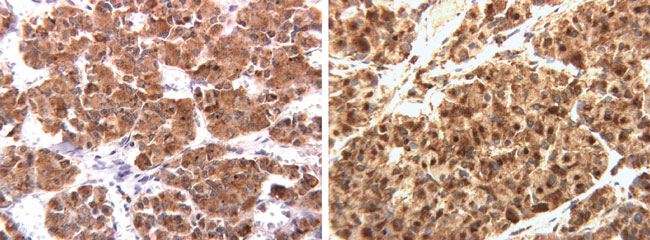

More than 90% of adenohypophysial cells were conclusively immunopositive for VEGF in every case. VEGF immunoreactivity was present in all of the specimens and there was no major difference between the pituitaries of pregnant or post-partum women and those of non-pregnant controls. Staining was limited to the cytoplasm. In comparison to those age-matched controls, no differences were noted in the intensity or frequency of immunostaining. Endothelial cells in the sections stained weakly with the VEGF antibody. The specificity of the antibody was confirmed by absent staining in the negative controls and successful absorption of the antibody with VEGF peptide which eliminated staining.

DISCUSSION

Neovascularization plays a crucial role in tumor cell proliferation, aggressiveness, invasion, metastasis formation and biologic behavior.14-16 Without adequate blood supply, tumor cells cannot multiply, spread to adjacent tissues and give rise to distant metastases.17,18 In the absence of adequate blood supply, tumor cells undergo apoptosis/necrosis.17 Increased vascularization is due to angiogenesis, neoformation of vessels from endothelial cells, precursor cells or stem cells.14,19-21 Angiogenesis is a complex multi-step process which involves extensive interplay between the components of the extracellular matrix, development, migration, proliferation and differentiation of the endothelial cells, formation of blood vessel lumen and production of the basement membrane.22 It was assumed previously that new blood vessels develop from preexisting capillaries; mature endothelial cells start to multiply and form new vessels.23 There is conclusive evidence that endothelial cell precursors from migrating bone marrow stem cells also play a major role in neovascularization.19-21 There are several factors which can stimulate, whereas others can inhibit angiogenesis and the balance between the various factors permits homeostasis.24-27 One of the most important factors is VEGF, which was reported to stimulate angiogenesis in several neoplasms.27,28 VEGF and probably other proteins are produced in and released from the tumor cells resulting in new vessel formation.27,28 VEGF is an endothelial cell mitogen, affecting endothelial cell proliferation, migration, differentiation and increasing vascular permeability.29 Recent evidence indicates that PRL can influence angiogenesis.30,31 The endothelial cells possess PRL receptors and some forms of PRL stimulates, whereas other forms inhibit vessel formation.32,33

Figure 1. CD-34 immunostaining demonstrating that microvessel densities did not increase in the adenophypophyses of pregnant women (A) as compared to non-pregnant controls (B).

While the role of angiogenesis and of VEGF has been extensively investigated in many pituitary tumors,34, 35 knowledge is limited on the role of neovascularization in non-neoplastic conditions.34 We investigated microvessel densities and VEGF immunoexpression in the adenohypophyses of pregnant and post-partum women. Our previous studies showed that the pituitaries of pregnant and post-partum women are increased in weight and size and contained more PRL immunopositive cells compared to age-matched non-pregnant controls.1,9 Thus, we anticipated an increase in microvessel densities and VEGF immunoexpression in the adenohypophyses of pregnant and post-partum women. Vidal et al.35 found no major change in the microvascular architecture and no difference in the microvessel density between the pituitaries of 10 pregnant women compared to those of non-pregnant controls.

Figure 2. No significant difference seen in the VEGF immunostaining in the pregnancy pituitary (A) compared to the age-matched control pituitary (B).

These authors also investigated microvessel surface densities expressed as the percentage of vessel circumference in direct contact with pituitary tissue. The results demonstrated that the lateral wings of pregnant women had a slightly higher microvessel surface density than the central mucoid wedge of the pars distalis.Our results showed that microvessel densities and VEGF immunoexpression did not increase in the adenophypophyses of pregnant or post-partum women as compared to non-pregnant controls.

Hypoxia is an important mechanism in initiation of new vessel formation.36 It appears that neither pregnant nor post-partum pituitaries are hypoxic. Additionally, it appears that in cases of PRL cell hyperplasia, the blood supply is satisfactory and there is no need for development of new vessels. It may well be that proliferating PRL cells in pregnant and post-partum pituitaries do not release an increased amount of VEGF and other angiogenic factors, thus not causing angiogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors are grateful to the Jarislowky and Lloyd Carr-Harris Foundations for their generous support. The authors also wish to thank Ms. Corrine Holubowich for the literature search.

REFERENCES

1.Scheithauer BW, Sano T, Kovacs KT, Young WF Jr, Ryan N, Randall RV, 1990 The pituitary gland in pregnancy: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 69 cases. Mayo Clin Proc 64: 461-474.

2.Gonzalez JG, Elizondo G, Saldivar D, Nanez H, Todd LE, Villarreal JZ, 1988 Pituitary gland growth during normal pregnancy: an in vivo study using magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Med 85: 217-220.

3.Goluboff LG, Ezrin C, 1969 Effect of pregnancy on the somatotroph and the prolactin cell of the human adenohypophysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 29: 1533-1538.

4.Friesen HG, Fournier P, Desjardins P, 1973 Pituitary prolactin in pregnancy and normal and abnormal lactation. Clin Obstet Gynecol 16: 25-45.

5.Erdheim J, Stumme E, 1909 ϋber die Schwangerschaftsveränderung der Hypophyse. Beitr Pathol Anat Allg Pathol 46: 1-132.

6.Aubert ML, Grumbach MM, Kaplan SL, 1974 Heterologous radioimmunoassay for plasma human prolactin (hPRL); values in normal subjects, puberty, pregnancy and pituitary disorders. Acta Endocrinol 77: 460-476.

7.Biswas S, Rodeck CH, 1976 Plasma prolactin levels during pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 83: 683-687.

8.Asa SL, Penz G, Kovacs K, Ezrin C, 1982 Prolactin cells in the human pituitary. A quantitative immunocytochemical analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 106: 360-363.

9.Stefaneanu L, Kovacs K, Lloyd RV, et al, 1992 Pituitary lactotrophs and somatotrophs in pregnancy: a correlative in situ hybridization and immunocytochemical study. Virchows Archiv B Cell Pathol 62: 291-296.

10.Erikson L, 1989 Growth hormone in human pregnancy. Maternal 24-hour serum profiles and experimental effects of continuous GH secretion. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl 147: 1-38.

11.Rotondo F, Scheithauer BW, Kovacs K, Bell DC, 2009 Rab 3B immunoexpression in human pituitary adenomas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 17: 185-188.

12.Rotondo F, Sharma S, Scheithauer BW, et al, 2010 Endoglin and CD-34 immunoreactivity in the assessment of microvessel density in normal pituitary and adenoma subtypes. Neoplasma 57: 590-593.

13.Lloyd RV, Scheithauer BW, Kuroki T, Vidal S, Kovacs K, Stefaneanu L, 1999 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in human pituitary adenomas and carcinomas. Endocr Pathol 10: 229-235.

14.Folkman J, 1990 What is the evidence that tumors are angiogenesis dependent? J NatL Cancer Inst 82: 4-6.

15.Denekamp J, 1993 Angiogenesis, neovascular proliferation and vascular pathophysiology as targets for cancer therapy. Br J Radiol 66: 181-196.

16.Furuya M, Yonemitsu Y, 2008 Cancer neovascularization and proinflammatory microenvironments. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 8: 253-265.

17.Pang RW, Poon RT, 2006 Clinical implications of angiogenesis in cancers. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2: 97-108.

18.Eichhorn ME, Kleespies A, Angele MK, Jaunch KW, Bruns CJ, 2007 Angiogenesis in cancer: molecular mechanisms, clinical impact. Langenecks Arch Surg 392: 371-379.

19.Ribatti D, 2004 The involvement of endothelial progenitor cells in tumor angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med 8:294-300.

20.Schatteman GC, Awad O, 2004 Hemangioblasts, angioblasts and adult endothelial cell progenitors. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 276: 13-21.

21.Dome B, Timar J, Ladanyi A, et al, 2009 Circulating endothelial cells, bone-marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells and proangiogenic hematopoietic cells in cancer: from biology to therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 69: 108-124.

22.Bussolino F, Mantovani A, Persico G, 1997 Molecular mechanisms of blood vessel formation. Trends Biochem Sci 22: 251-256.

23.Risau W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature 386: 671-674.

24.Hiraoka N, Allen E, Apel IJ, Gyetko MR, Weiss SJ, 1998 Matrix metalloproteinases regulate neovascularization by acting as pericellular fibrinolysins. Cell 95: 365-377.

25.D’Amato RJ, Loughnan MS, Flynn E, Folkman J, 1994 Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 4082-4085.

26.Bouck N, Stellmach V, Hsu SC, 1996 How tumors become angiogenic. Adv. Cancer Res 69: 135-174.

27.Neufeld G, Cohen T, Gengrinovitch S, Poltorak Z, 1999 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J 13: 9-22.

28.Dvorak HF, 2002 Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor: a critical cytokine in tumor angiogenesis and a potential target for diagnosis and therapy. J Clin Oncol 20: 4368-4380.

29.Ferrara N, Houck K, Jakeman L, Leung DW, 1992 Molecular and biological properties of the vascular endothelial growth factor family of proteins. Endocrine Rev 13: 18-32.

30.Das R, Vonderhaar BK, 1997 Prolactin as a mitogen in mammary cells. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2: 29-39.

31.Clevenger CV, Furth PA, Hankinson SE, Schuler LA, 2003 Role of prolactin in mammary carcinoma. Endocr Rev 24: 1-27.

32.Clapp C, Lopez-Gomez FJ, Nava G, et al, 1998 Expression of prolactin mRNA and of prolactin-like proteins in endothelial cells: Evidence for autocrine effects. J Endocrinol 158: 137-144.

33.Tabruyn SP, Nguyen NQ, Cornet AM, Martial JA, Struman I, 2005 The antiangiogenic factor, 16-kDa human prolactin, induces endothelial cell cycle arrest by acting at both the G0–G1 and the G2-M phases. Mol Endocrinol 19: 1932-1942.

34.Lloyd RV, Vidal S, Horvath E, Kovacs K, Scheithauer BW, 2003 Angiogenesis in normal and neoplastic pituitary tissues. Microsc Res Tech 60: 244-250.

35.Vidal S, Scheithauer BW, Kovacs K, 2000 Vascularity in nontumorous human pituitaries and incidental microadenomas: a morphometric study. Endocr Pathol 11: 215-227.

36.Hickey MM, Simon MC, 2006 Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factors. Curr Top Dev Biol 76: 217-257.

Fabio Rotondo, BSc, Department of Laboratory Medicine,

Division of Pathology, St. Michael’s Hospital,

30 Bond Street, Toronto, ON, Canada, M5B1W8,

Tel.: 416-864-5851, Fax: 416-864-5648,

e-mail: rotondof@smh.ca

Received 22-11-2012, Accepted 09-04-2013