Unit of Internal Medicine and Endocrinology, Fondazione Salvatore Maugeri I.R.C.C.S., Chair of Endocrinology, University of Pavia, Italy

Autoimmunity, Environment and thyroid autoimmunity, Experimental autoimmune thyroiditis, Genes of thyroid autoimmunity, Graves’ disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Thyroid, Thyroid antibodies

Introduction

Autoimmune diseases are a group of heterogeneous disorders characterized by abnormal lymphocytic activation directed against self-tissues. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT) and Graves’ disease (GD) are two of the most common clinical expressions of organ-specific autoimmunity.1They fulfill all the required criteria for autoimmune diseases including: 1) infiltration of the thyroid by lymphocytes, which are auto-reactive to thyroid antigens; 2) presence of circulating thyroid autoantibodies; 3) immunological overlap with other autoimmune diseases; 4) a story of familiar occurrence, mainly in females; 5) the possibility to produce both experimental autoimmune thyroiditis and, to a lesser extent, Graves’ disease in laboratory animals.2

The three main thyroid auto-antigens, which were identified several decades ago, are thyroglobulin (Tg), the organ-specific enzyme thyroid peroxidase (TPO), and the TSH-receptor (TSH-R).3 In the first years of this century, the sodium-iodide symporter was also shown to behave as a thyroid-specific auto-antigen.4 More recently, autoantibodies to pendrin, an iodide transporter located at the apical pole of thyroid follicular cells, were identified in the majority of patients with HT and GD.5

Basic mechanisms in the development of thyroid autoimmunity

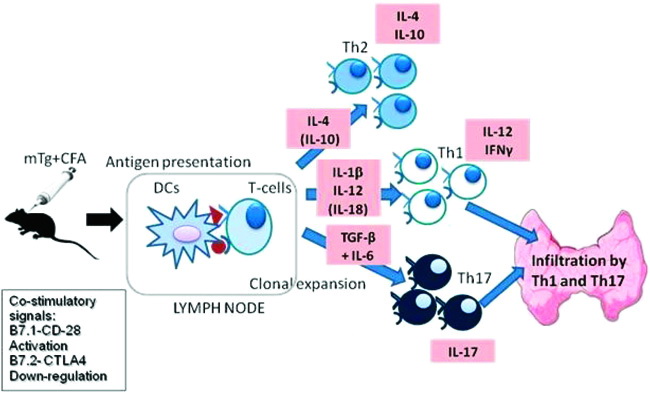

Most of our current knowledge on the basic mechanisms of thyroid autoimmunity derives from data obtained studying experimental models of autoimmune disease, mainly in mice. Experimental autoimmune thyroiditis (EAT) in mice can be induced by immunization with mouse Tg emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant. Antigen presenting cells (APC), such as dendritic cells (DC), present immunogenic epitopes of Tg to T cells in the context of Class II major hystocompatibility molecules (MHC). Co-stimulatory signals are also required, which may result in either activation or down-regulation of T-cells. Based on the type of cytokines secreted by these DCs, a Th1, Th2, or a Th17 immune response can be initiated. Th1 cells predominantly secrete IFN-γ and IL-12, whereas Th2 cells secrete IL-4 and IL-10. Th17 cells secrete IL-17. Th1 and Th17 cells have been shown to infiltrate the thyroid, resulting in chronic inflammation and eventually death of the thyrocytes in EAT (Figure 1).6-10 CD4+ T cells are the major type of lymphocytic cells infiltrating the gland in thyroid autoimmune diseases. CD4 + T cells comprise a functionally heterogeneous population of T effector cells (Teff), being responsible for the development of thyroiditis and a smaller population (10%) of T regulatory cells (Tregs), which express CD25 (the IL-2 receptor α). Tregs are critical for maintaining peripheral tolerance and are identified by their expression of Foxp3, a transcription factor which is necessary and sufficient for Treg development. These cells typically secrete the cytokines IL-10 and Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) to induce tolerance. Neonatal thymectomy (at 3 days) and irradiation result in a multi-organ autoimmune disease, thus providing evidence for natural Tregs. The role of these cells is to prevent the development of organ-specific autoimmunity. Tregs are kept at a basal state of activation by low levels of circulating auto-antigen; the homeostatic level is sufficient to prevent the development of autoimmunity, but the clonal balance between Tregs and auto-reactive T cells could be overcome by immunogenic stimuli, such as the administration of mTG and adjuvant.11

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the immune events occurring after immunization of mice with mouse Tg (mTg) in Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA). Co-stimulatory signals include B7-1 and B7-2. B7-1 (also known as CD80) is a protein found on activated B cells and monocytes that provides a co-stimulatory signal necessary for T cell activation and survival after binding with the CD28 protein on the T cell surface. B7-2 (also known as CD86) is a protein expressed on antigen-presenting cells that down-regulates the immune response by binding with CTLA-4, a protein on the T cell surface. EAT: experimental autoimmune thyroiditis; DCs: dendritic cells; IFN: interferon; IL: interleukin; TGF: transforming growth factor.

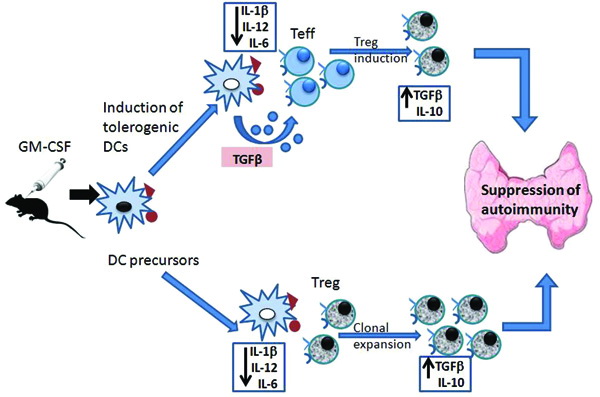

As demonstrated by the group of Prabhakar,12 treatment of mTg primed mice with granulocyte- macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) induces semi-matured tolerogenic DCs that are characterized by reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-12 and increased levels of TGF-β. These tolerogenic DCs, instead of activating pathogenic Teff, induce and expand Tregs. Tregs produce IL-10 and TGF-β, two regulatory cytokines, which, by counteracting the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines, result in the suppression or prevention of EAT (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the immune events occurring during the induced down-regulation of EAT by GMCSF. EAT: experimental autoimmune thyroiditis; GM-CSF: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; Teff: effector T cells; Tregs: regulatory T cells; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; DCs: dendritic cells; IL: interleukin.

Experimental evidence in mice demonstrated that, apart from Tg, TPO is also a major antigen in chronic autoimmune thyroiditis. Indeed, transgenic, TAZ10, mice expressing a human T-cell receptor-specific for a cryptic TPO epitope, spontaneously develop chronic autoimmune thyroiditis. This thyroid autoimmunity model is Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC II) restricted, but occurs independently from mature B cells and antibodies.13 Moving from these experiments in mice, the group of Schott recently studied TPO and Tg epitope-specific CD8+ T-cells in patients with HT, who were investigated both at the time of diagnosis and after a long-lasting disease. To this end, they synthesized six different human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2 restricted, TPO- or Tg-specific tetramers. The frequency of peripheral TPO- and Tg-specific CD8-positive T cells was significantly higher in HLA-A2-positive HT patients (2.8 + 9.5%) compared with HLA-A2-negative HT patients (0.5 + 0.7%), HLA-A2-positive non-autoimmune goiter patients (0.2 + 0.4%), and HLA-A2-positive healthy controls (0.1 + 0.2%). The frequency of Tg-specific T cells (3.0%) was very similar to that of TPO-specific CD8-positive T cells (2.9%). Subgroup analyses revealed a steady increase of the number of epitope-specific CD8-positive T cells from 0.6 + 1.0% at initial diagnosis up to 9.4 + 18.3% in patients with long-lasting disease. Analyses of the number of thyroid-infiltrating cells as well as the cytotoxic capacity revealed a similar picture for TPO- and Tg-specific T cells. These data demonstrate that both TPO- and Tg-specific CD8-positive T cells are involved in the disease process of HT. Interestingly enough, Tg-specific T-cells were elevated in the peripheral blood at the time point of clinical disease manifestation, whereas a reverse distribution was observed in the thyroid aspirates. This phenomenon may suggest a role of Tg-specific T cells at disease initiation. During disease progression, TPO-specific T-cells would acquire an incremental role due to epitope spreading. Taken together, this study supports the view that in HT a combined TPO- and Tg-specific cytotoxic immune response does occur.14

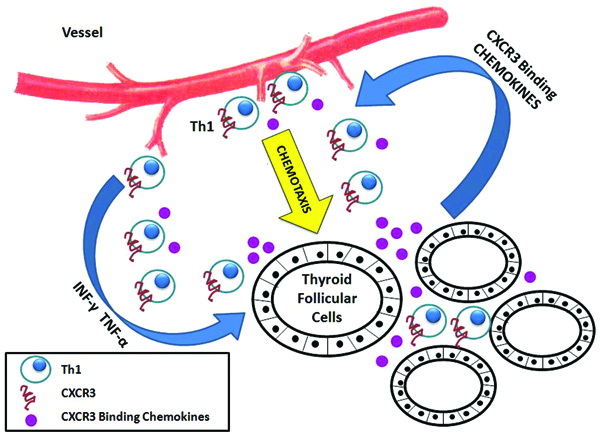

In the last few years, evidence was also accumulated supporting the concept that INF-γ inducible chemokines, such as CXCL10, play an important role in the initial stages of thyroid autoimmunity. When stimulated by INF-γ, thyroid follicular cells secrete CXCL10, which in turn recruits into the thyroid Th1 lymphocytes expressing CXCR3 and secreting INF-γ, thus establishing a loop which reinforces and maintains the autoimmunity process (Figure 3).15

Figure 3. Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism of lymphocyte recruitment by CXCR3 binding chemokines in thyroid autoimmunity. Thyroid follicules cells secrete CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 upon stimulation with IFN-γ and TNF-α. Chemokines, in turn, drive chemotaxis from blood vessels of T cells expressing the chemokine receptor CXCR3. This particular subset of T cells shows a prevalent Th1 immune phenotype and produces IFN-γ, thus perpetuating the inflammatory process. This loop of events supports the active role played by thyroid follicular cells in determining the specificity of the infiltrating lymphocytes and in maintaining the autoimmune process. IFN-γ, interferon-γ; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.15

Cellular and humoral effector mechanisms in thyroid autoimmunity

Cell damage mechanisms in thyroid autoimmunity involve: antibody dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC); Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis of thyroid cells (so-called suicide or fratricide); the direct cytotoxic effect of CD8+ and CD4+ cells, which is MHC-I and MHC-II restricted, respectively (also so-called homicide); and the granule-exocytosis pathway (perforins, granzymes).16Lymphokine-activated killer cells are also involved. Humoral mechanisms include the thyroid stimulating or TSH blocking effect of TSH-R antibodies 17and the complement-mediated cytotoxic effect of TPO-antibodies.18 The eventual destruction of thyroid follicular cells is responsible for the development of hypothyroidism in chronic autoimmune thyroiditis.3,19 TSHR antibodies with thyroid stimulating activity are the main effectors of hypothyroidism in Graves’ disease and may additionally be involved in the pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy.20-22

Hypothyroidism can also occur by being mediated through the inhibiting effect of cytokines on thyroid hormone synthesis. According to this model, clinical hypothyroidism results from a chronic inhibition of thyroid function, which is induced by exposure of the thyroid to pro-inflammatory cytokines like IFN-γ and TNF-α. These factors can be present in the thyroid also independently of infiltrating lymphocytes. The novelty of this non-classical model is that thyroid atrophy is shown to be the consequence of thyroid hypofunction rather than the cause of it.23

Loss of self-tolerance to the thyroid in humans

Moving from mice to humans, the main question to be answered is how tolerance to the ”selfthyroid” is lost. According to the clonal selection theory, in the early stage of fetal-neonatal development most auto-reactive T-cells are eliminated within the thymus by negative selection.3 This mechanism is usually referred to as central tolerance. The few escaped auto-reactive clones that migrate to the periphery are controlled by several mechanisms of peripheral tolerance involving ignorance (they remain non-responsive to antigenic stimulation), anergy, activation-induced cell death, and active suppression by Tregs.

Similarly to other autoimmune diseases, loss of tolerance to thyroid antigens involves a complex interplay between genetic background and environmental factors.24,25

Role of genetics

The role of genetics is suggested by the high frequency of autoimmune thyroid diseases affecting family members and by a significantly higher concordance of autoimmune thyroid diseases in monozygotic (HT = 55%; GD = 35%) compared to dizygotic (HT = 0%; GD = 3%) twins.26-28 The fact that concordance is not 100% in monozygotic twins indicates that environmental factors also play an important role in the etiology of autoimmune thyroid diseases. Indeed, it is assumed that autoimmune thyroid diseases are caused by the combined effects of multiple susceptibility genes and environmental factors which affect both the thyroid and the systemic immune system.25,28,29 Several susceptibility genes have been identified by whole candidate gene analysis, genome linkage studies, genome-wide association studies, and whole-genome sequencing techniques (Table 1).25 These genes are classified as non-specific immune-related genes and thyroid-specific genes. The immune-related genes are divided into two groups: immunological synapse genes and regulatory T-cells genes.

The immunological synapse is the interface between APCs and T-cells that is formed during T-cell activation. It is a complex interface involving peptide antigen bound to an MHC-II molecule and to the T-cell receptor, co-stimulatory molecules, receptors on the APC and T-cells, integrins, and other molecules.30 Some alleles of the HLA-DR gene can facilitate antigen presentation; in particular arginine at position 74 of the HLA-DRb1 chain (DRb-Arg74) confers susceptibility to GD.31 The CD40 gene was also reported as a susceptibility gene for GD. CD40 is expressed primarily on B-cells and other APCs and plays a fundamental role in B-cell activation and antibody secretion.32,33 The CTLA-4 gene is a major negative regulator of T-cell activation. Some polymorphisms of CTLA-4 have been shown to reduce the suppression of T-cell activation by antigens.34 The Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase-22 (PTPN22) gene plays a role as negative regulator of T-cell activation.35 Genes for regulatory T-cells (Treg) that can predispose to autoimmune thyroid diseases are FOXP3, a key gene in the differentiation of T-cells in Tregs, and CD25. Among thyroid-specific genes, those for thyroglobulin and the TSH-R play a role in susceptibility to thyroid autoimmunity. Tg is one of the main targets of the immune response in autoimmune thyroid diseases. Amino-acids variants in the Tg gene (A734S, V1027M, W1999R) can result in altered degradation of Tg in endosomes, inducing a pathogenic Tg repertoire (unique Tg peptides binding to specific HLA-DR pockets). Studies also suggest a role of the TSH-R gene’s variant that can predispose to Graves’ disease.25

What this enormous investigative effort has demonstrated is that most identified genes have a very minor effect. With the exception of the DRb1-Arg74HLA variant (with OR for GD >5), all other genes involved in thyroid autoimmunity give very low OR (<1.5). To explain the strong genetic susceptibility to autoimmune thyroid diseases, three hypotheses have been formulated: (i) an individual needs to inherit many genes of small effect; (ii) gene-gene interaction may occur resulting in a combined OR that is significantly higher than that expected with an additive effect alone; (iii) a subset effect (also called genetic heterogeneity) may be involved producing a high OR only in a subset of patients with autoimmune thyroid diseases. As a matter of fact, really significant genes, which means that the autoimmune disease should not occur without some of the responsible polymorphisms, are still to be identified.36,25A possible exception is the autoimmune regulator gene (AIRE). Its products mediate the transcription of many self-antigens in medullary epithelial cells in the thymus. Decreased AIRE expression may lead to a decrease in thymic expression of Tg and other thyroid auto-antigens, resulting in the peripheral escape of auto-reactive T cells.37 Indeed, an autosomal dominant allele of AIRE has been associated with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.38

The complex role of epigenetic control on gene transcription is far from being exhaustively explored, while the influence of X chromosome inactivation on thyroid autoimmunity also remains to be clarified.

Role of the environment

As recently reviewed by Duntas, an array of environmental factors have been inculpated for their stimulatory effect on thyroid autoimmunity (Table 2).24 Some of these factors, such iodine excess, selenium deficiency, tobacco smoking and, possibly, industrial pollutants, exert their effects mainly at a population level. Infective agents, immune-modulatory drugs, and stress are probably more relevant for the individual development of autoimmune thyroid diseases.

Recent hypotheses on the pathogenesis of thyroid autoimmunity

Innate immune activation (the danger hypothesis)

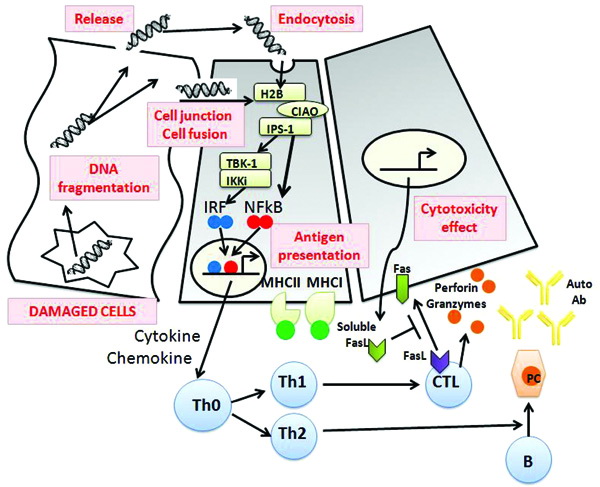

Endogenous molecules, also referred to as danger (damage)-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are produced by dying cells, may induce innate immune responses. DAMPs include genomic DNA fragments, heat shock proteins, high mobility group B1 proteins, uric acid, collagen, and hyaluronic acid. Toll-like receptors of innate immunity are also present on thyrocytes and, by recognizing DAMPs, may activate the innate immune response. Genomic DNA (but also RNA) may behave as a DAMP. When introduced into the cytosol of a viable cell, double-stranded DNA is recognized by DNA sensors (such as histone H2B) and can activate immune responses by up-regulating the genes for MHC, co-stimulatory molecules, transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP-1), immune proteasome subunit LMP2, signal transducer of transcription 1 (STAT-1), IFN regulatory factor (IRF), protein kinase R, and type-1 IFNs. This process of autophagy also allows the processing and delivery of cytosolic antigens to be loaded on MHC-II molecules, thus enabling thyroid cells to present their antigens (such as the TSH-R) to CD 4 + T cells (Figure 4).28

Figure 4. The model of autophagy-mediated development of thyroid autoimmunity proposed by Kawashima.28 Fragments of genomic DNA (double stranded DNA, dsDNA) released from the nuclei of damaged cells may either directly leak into neighboring cells via cell junctions or cell fusion or be released into the follicular lumen and endocytosed with colloid. Extrachromosomal histone H2B recognizes misplaced dsDNA in the cytosol through COOH-terminal importin 9-related adaptor-organizing histone H2B and IPS-1 (CIAO), and then signals such as IRF and NF-kB are activated via TBK1/IKKi. These result in the production of IFNs, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines followed by MHC expression and lymphocytic infiltration. As a result, activation of T and B lymphocytes and Fas-mediated apoptosis are induced, which may contribute to initiating the autoimmune reaction. IFN: interferon; MHC: major histocompatibility complex; PC: Plasma Cell.

The danger hypothesis has been put forward to explain the possible role of thyroid follicular cells as self-antigen presenting cells to the immune system, the old Bottazzo’s hypothesis.39 In the past, attempts to establish an experimental model of Graves’ disease by immunizing mice with the TSH-R or derived peptides largely failed. On the other hand, immunization with non-classical APC (fibroblasts) co-expressing MHC-II and TSH-R,40 or genetic vaccination using TSH-R expressing plasmid, or infection with adenovirus expressing a TSH-R subunit proved successful.40,42 These experimental models of Graves’ disease imply the requirement for processing TSH-R as an endogenous antigen and loading it onto MHC-II for presentation to CD4+ T cells. A role for autophagy has been suggested by Kawashima et al. for the spontaneous development of Graves’ disease in humans.28

Fetal microchimerism

Fetal cell microchimerism (FCM) was also implicated in the pathogenesis of thyroid autoimmune diseases.43FCM is due to the passage of cells from the fetus to the mother. Fetal cells commonly appear in the maternal circulation early in gestation (4-5 weeks). FCM involve T (CD4+ and CD8+) and B cells, monocytes, macrophages, NK cells, CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells,CD34+/CD38+progenitor stem cells, mesenchimal cells, and endothelial progenitor cells. Fetal cells can persist in the mother for more than 27 years after the partum. While not producing a graft versus host reaction, fetal cells might mature in the maternal thymus. The presence of these engrafted cells or their proteins could break tolerance or could impair the function of host autoantigen-specific immunoregulatory cells. Such a mechanism could also explain the exacerbation of autoimmune reactivity in the post-partum period and later in life.

Evidence favoring a pathogenic role of FCM in thyroid autoimmunity stems from studies indicating that: (i) A significantly higher number of FCM was found within the thyroid gland of women with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease compared with women without thyroid autoimmunity;44,45 (ii) Male cells can be detected in the peripheral blood of both Graves’ disease patients and healthy women of reproductive age;46 (iii) In a murine model of EAT, fetal immune cells (T cell and dendritic cell lineages) were found to accumulate in maternal thyroids;47 (iv) The thyroid autoimmunity susceptibility markers, HLA DQA1*0501-DQB1*0201, and DQB1*0301, are more common in mother-child pairs positive for FCM;46 (v) One case-control study indicated parity as a potential risk factor for AITD.48 By contrast, three large epidemiological community-based studies failed to demonstrate an association between pregnancy, parity, abortion, and the presence of thyroid autoantibodies or thyroid dysfunction, indicating that FCM could be a marginal phenomenon.49-51

The hygiene hypothesis

The hygiene hypothesis suggests that people born and living in countries with a high socioeconomic standard and, as a consequence, being exposed to a lower burden of infectious agents during childhood might be more prone to develop thyroid autoimmunity.

An epidemiological study comparing the prevalence of thyroid antibodies in the genetically similar populations of Russian Karelia and Finland supports this hypothesis. Indeed, the prevalence of thyroid antibodies was significantly higher in schoolchildren from Karelia compared to their counterparts in Finland. This result supports the idea that the Russian environment, which is characterized by inferior prosperity and standard of hygiene, may provide a protection against thyroid autoimmunity.52

Conclusions

Over half a century has elapsed since the 1956 identification of thyroglobulin antibodies and the devising of the first experimental model of autoimmune thyroiditis. Since then, an incredible amount of experimental work has led to an ever deeper understanding of the nature of thyroid auto-antigens, the main immune mechanisms responsible for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease, their genetics, and their environmental risk factors. Yet, in the majority of genetically predisposed people the individual trigger of thyroid autoimmunity remains obscure. Similarly, effective prevention strategies still remain to be established and, hopefully, will be the target of future studies.

REFERENCES

1. Stathatos N, Daniels GH, 2012 Autoimmune thyroid disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol 24: 70-75.2. Rose NR, Bona C, 1993 Defining criteria for autoimmune diseases (Witebsky’s postulates revisited). Immunol Today 14: 426-430.

3. Weetman AP, 2003 The mechanisms of autoimmunity in endocrinology: application to the thyroid gland. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 64: 26-27.

4. Tonacchera M, Agretti P, Ceccarini G, et al, 2001 Autoantibodies from patients with autoimmune thyroid disease do not interfere with the activity of the human iodide symporter gene stably transfected in CHO cells. Eur J Endocrinol 144: 611-618.

5. Yoshida A, Hisatome I, Taniguchi S, et al, 2009 Pendrin is a novel autoantigen recognized by patients with autoimmune thyroid diseases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 442-448.

6. Ganesh BB, Bhattacharya P, Gopisetty A, Prabhakar BS, 2011 Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis and suppression of thyroid autoimmunity. J Interferon Cytokine Res 31: 721-731.

7. Vasu C, Dogan RN, Holterman MJ, Prabhakar BS, 2003 Selective induction of dendritic cells using granulocyte macrophagecolony stimulating factor, but not fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor 3-ligand, activates thyroglobulin-specific CD4+ /CD25 + T cells and suppresses experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. J Immunol 170: 5511-5522.

8. Kroemer G, Hirsch F, Gonzalez-Garcia A, Martinez C, 1996 Differential involvement of Th1 and, Th2 cytokines in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity 24: 25-33.

9. Langrish CL, et al, 2005 IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med 201: 233-240.

10. Yoshimoto T, Takeda K, Tanaka T, et al, 1998 IL-12 up-regulates IL-18 receptor expression on T cells, Th1 cells, and B cells: synergism with IL-18 for IFN-gamma production. J Immunol 161: 3400-3407.

11. Kong YC, Morris GP, Brown NK, Yan Y, Flynn JC, David CS, 2009 Autoimmune thyroiditis: a model uniquely suited to probe regulatory T cell function. J Autoimmun 33: 239-246.

12. Gangi E, Vasu C, Cheatem D, Prabhakar BS, 2005 IL-10-producing CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells play a critical role in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-induced suppression of experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. J Immunol 174: 7006-7013.

13. Quaratino S, Badami E, Pang YY, et al, 2004 Degenerate self-reactive human T-cell receptor causes spontaneous autoimmune disease in mice. Nat Med 10: 920-926.

14. Ehlers M, Thiel A, Bernecker C, et al, 2012 Evidence of a combined cytotoxic thyroglobulin and thyroperoxidase epitope-specific cellular immunity in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97: 1347-1354.

15. Rotondi M, Chiovato L, Romagnani S, Serio M, Romagnani P, 2007 Role of chemokines in endocrine autoimmune diseases. Endocr Rev 28: 492-520.

16. Tomer Y, Huber A, 2009 The etiology of autoimmune thyroid disease: a story of genes and environment. J Autoimmun 32: 231-239.

17. Mariotti S, Chiovato L, Vitti P, et al, 1989 Recent advances in the understanding of humoral and cellular mechanisms implicated in thyroid autoimmune disorders. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 50(1 Pt 2): S73-84.

18. Chiovato L, Bassi P, Santini F, et al, 1993 Antibodies producing complement-mediated thyroid cytotoxicity in patients with atrophic or goitrous autoimmune thyroiditis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 77: 1700-1705.

19. Dayan CM, Daniels GH, 1996 Chronic autoimmune thyroiditis. N Engl J Med 335: 99-107.

20. Bartalena L, Tanda ML N, 2009 Clinical practice. Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Engl J Med 360: 994-1001.

21. Wiersinga WM, 2011 Autoimmunity in Graves’ ophthalmopathy: the result of an unfortunate marriage between TSH receptors and IGF-1 receptors? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96: 2386-2394.

22. Marino M, Chiovato L, Pinchera A 2006 Graves’ disease. In: DeGroot LJ and Jameson JL, Endocrinology, Elsavier, Philadelphia; pp. 1995-2028.

23. Caturegli P, Kimura H, 2010 A nonclassical model of autoimmune hypothyroidism. Thyroid 20: 3-5.

24. Duntas LH, 2008 Environmental factors and autoimmune thyroiditis. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 4: 454-460.

25. Tomer Y, 2010 Genetic susceptibility to autoimmune thyroid disease: past, present, and future. Thyroid 20: 715-725.

26. Brix TH, Kyvik KO, Hegedus L, 2000 A population-based study of chronic autoimmune hypothyroidism in Danish twins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 536-539.

27. Brix TH, Kyvik KO, Christensen K, Hegedus L, 2001 Evidence for a major role of heredity in Graves’ disease: a population-based study of two Danish twin cohorts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 930-934.

28. Kawashima A, Tanigawa K, Akama T, Yoshihara A, Ishii N, Suzuki K, 2011 Innate immune activation and thyroid autoimmunity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96: 3661-3671.

29. Barbesino G, Chiovato L, 2000 The genetics of Hashimoto’s disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 29: 357-374.

30. Dustin ML, 2008 T-cell activation through immunological synapses and kinapses. Immunol Rev 221: 77-89.

31. Ban Y, Davies TF, Greenberg DA, et al, 2004 Arginine at position 74 of the HLA-DRb1 chain is associated with Graves’ disease. Genes Immun 5: 203-208.

32. Armitage RJ, Macduff BM, Spriggs MK, Fanslow WC, 1993 Human B cell proliferation and Ig secretion induced by recombinant CD40 ligand are modulated by soluble cytokines. J Immunol 150: 3671-3680.

33. Arpin C, Déchanet J, Van Kooten C, et al, 1995 Generation of memory B cells and plasma cells in vitro. Science 268: 720-722.

34. Teft WA, Kirchhof MG, Madrenas J, 2006 A molecular perspective of CTLA-4 function. Annu Rev Immunol 24: 65-97.

35. Cloutier JF, Veillette A, 1999 Cooperative inhibition of T-cell antigen receptor signaling by a complex between a kinase and a phosphatase. J Exp Med 189: 111-121.

36. Davies TF, 2007 Really significant genes for autoimmune thyroid disease do not exist--so how can we predict disease? Thyroid 17: 1027-1029.

37. Anderson MS, 2008 Update in endocrine autoimmunity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93: 3663-3670.

38. Cetani F, Barbesino G, Borsari S, et al, 2001 A novel mutation of the autoimmune regulator gene in an Italian kindred with autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy, acting in a dominant fashion and strongly cosegregating with hypothyroid autoimmune thyroiditis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 4747-4752.

39. Hanafusa T, Pujol-Borrell R, Chiovato L, Russell RC, Doniach D, Bottazzo GF, 1983 Aberrant expression of HLA-DR antigen on thyrocytes in Graves’ disease: relevance for autoimmunity. Lancet 2: 1111-1115.

40. Shimojo N, Kohno Y, Yamaguchi K, et al, 1996 Induction of Graves-like disease in mice by immunization with fibroblasts transfected with the thyrotropin receptor and a class II molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 11074-11079.

41. McLachlan SM, Nagayama Y, Rapoport B, 2005 Insight into Graves’ hyperthyroidism from animal models. Endocr Rev 26: 800-832.

42. Nagayama Y, 2005 Animal models of Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Endocr J 52: 385-394.

43. Fugazzola L, Cirello V, Beck-Peccoz P, 2012 Microchimerism and endocrine disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97: 1452-1461.

44. Klintschar M, Schwaiger P, Mannweiler S, Regauer S, Kleiber M, 2001 Evidence of fetal microchimerism in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 2494-2498.

45. Ando T, Imaizumi M, Graves PN, Unger P, Davies TF, 2002 Intrathyroidal fetal microchimerism in Graves’ disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87: 3315-3320.

46. Renne C, Ramos Lopez E, Steimle-Grauer SA, et al, 2004 Thyroid fetal male microchimerism in mothers with thyroid disorders: presence of Y-chromosomal immunofluorescence in thyroid infiltrating lymphocytes is more prevalent in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease than in follicular adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 5810-5814.

47. Imaizumi M, Pritsker A, Unger P, Davies TF, 2002 Intrathyroidal fetal microchimerism in pregnancy and postpartum. Endocrinology 143: 247-253.

48. Friedrich N, Schwarz S, Thonack J, John U, Wallaschofski H, Volzke H, 2008 Association between parity and autoimmune thyroiditis in a general female population. Autoimmunity 41: 174-180.

49. Walsh JP, Bremner AP, Bulsara MK, et al, 2005 Parity and the risk of autoimmune thyroid disease: a community-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 5309-5312.

50. Bulow Pedersen I, Laurberg P, Knudsen N, et al, 2006 Lack of association between thyroid autoantibodies and parity in a population study argues against microchimerism as trigger of thyroid autoimmunity. Eur J Endocrinol 154: 39-45.

51. Sgarbi JA, Kasamatsu TS, Matsumura LK, Maciel RMB, 2010 Parity is not related to autoimmune thyroid disease in a population-based study of Japanese-Brazilians. Thyroid 20: 1151-1156.

52. Kondrashova A, Viskari H, Haapala AM, et al, 2007 Serological evidence of thyroid autoimmunity among schoolchildren in two different socioeconomic environments. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93: 729-734.

Address for correspondence:

Luca Chiovato, M.D., Ph.D., Unit of Internal Medicine and

Endocrinology, Fondazione Salvatore Maugeri I.R.C.C.S.,

Chair of Endocrinology, University of Pavia, Via S. Maugeri

10, I-27100, Pavia, Italy, Tel.: +39-0382-592240,

Fax: +39-0382-592692, e-mail: lchiovato@fsm.it

Received 27-08-12, Accepted 23-11-12